The proportion of people around the world with a disability is getting larger. However, businesses have generally failed to keep pace and enjoy the advantages of a more inclusive approach at home – and when sending employees overseas. Dominic Weaver reports on progress and how companies, including movers, can change for the better

Estimates for the proportion of people in the world who are categorised as having a disability varies widely, ranging from 10 per cent to almost two-fifths of the global population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the latter figure includes an estimated 1.3 billion people affected by blindness or other visual impairment and need glasses, 466 million with disabling deafness and hearing loss, and 200 million people with an intellectual disability (having an IQ of below 75); representing 17 per cent, six per cent and 2.6 per cent of the global population, respectively. Meanwhile, 75 million people, or one per cent of the world’s inhabitants, need to use a wheelchair every day.

These are hugely significant numbers – and they are increasing, too. Overall, the global population is ageing (particularly in the developed world), with 962 million people over the age of 60 in 2017, twice the number in 1980, and forecast to rise to 2.1 billion people in this category by 2050; this will inevitably mean more people with disability issues.

This growth is also being driven because of an increase in ‘invisible’ disabilities, which are not immediately obvious but have an impact on quality of life, such as mental health issues and deafness. According to the World Bank, approximately 10 per cent of people in the US have such a condition. COVID-19 has swollen these numbers further, causing a dramatic upswing in mental health issues such as anxiety and depression; according to an August report released by the UK Office of National Statistics, one in five people are showing symptoms of depression, compared with one in 10 before the pandemic.

In addition, a growing number around the world are suffering from chronic illnesses; and our overall understanding and measurement of disability is getting better.

In the world of international work, the provision of support for diversity and inclusivity (D&I) has been getting better, too. This includes work by progressive moving and relocation businesses. Hong Kong-headquartered Crown World Mobility, for example, last year earmarked D&I as a key trend – while, anecdotally, more women are taking on high-level positions in the industry, and more minority ethnic groups are being chosen for international assignments.

However, plenty of work remains to be done, particularly in the field of disability. A recent FIDI blog quotes training company Learnlight: ‘While 15 per cent of the US workforce has some form of mental or physical disability, disabled assignees represent a negligible proportion of the international workforce.’

And, when it comes to international assignments, it seems that people with disabilities are under-represented on an even larger scale. FIDI recently asked a handful of Affiliates if their customers had specific policies in place to encourage the placement and support of more people with disabilities; none did – despite most having general equal employment opportunity (EEO) policies.

So, why are global businesses holding back from sending employees with disabilities on international assignments?

It seems likely that a large part of the answer to this question lies in the wide variations in the standards, attitudes and ease of accessibility that people with disabilities face in different countries. The picture is far from universally positive. When a wheelchair user asked readers of the website International Living for their recommendations of good locations for overseas retirement, everyone who responded advised that their own country would not be a good choice.

Developing countries are generally more challenging for accessibility and policy support, although many developed nations continue to fall behind in accessibility

Relocating to a new country is usually difficult. When an assignee moves, research and planning takes place to ensure they can access the health, education, transport, information and work services they need; when an assignee moves with a disability, there can be further physical and mental challenges and an additional level of complexity for them and their employers to navigate, as well as additional costs.

Global executive Jenny Ford [not her real name] needs support for her disability and has moved several times during her career so far. She says in addition to the general bias and discrimination that she experiences as the result of her disability, there is also a widespread lack of access to disability-friendly facilities in public and office spaces in many locations around the world.

She says: ‘Developing countries are generally more challenging for accessibility and policy support, although many developed nations continue to fall behind in accessibility.’

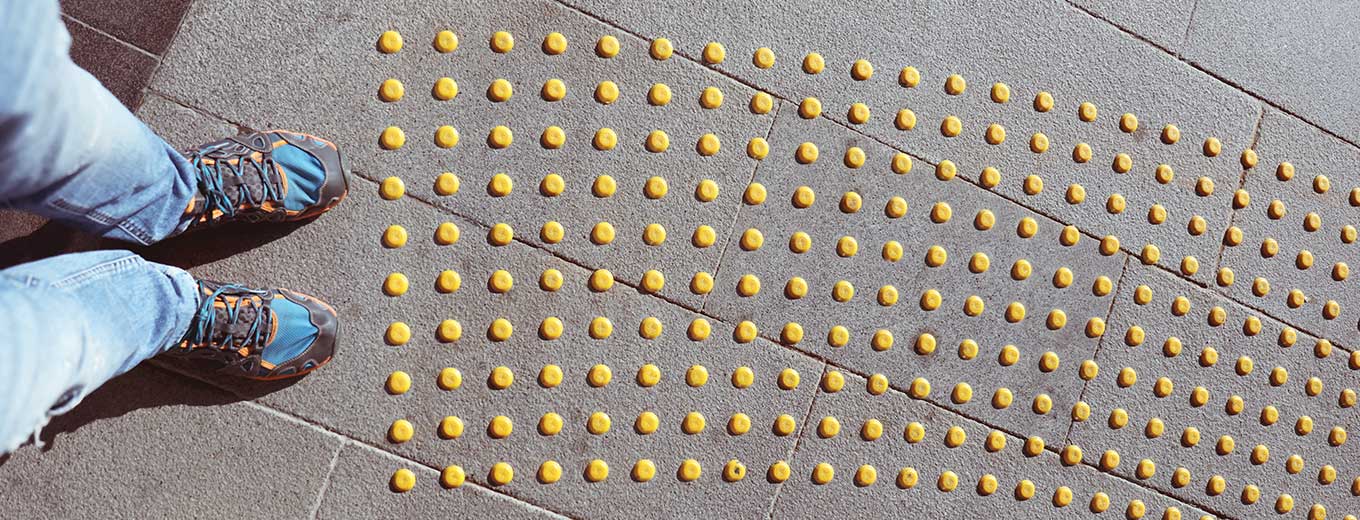

It has been said that it is not people who have a disability, it is the city in which they live (or, indeed, the premises in which they work). There have been encouraging moves made in progressive cities around the world, where previously inaccessible facilities such as subways and other infrastructure have been upgraded, opening them up to include people with a range of issues. According to the website travelpulse.com, these include Las Vegas, which provides some of the world’s most accessible hotel accommodation; Sydney with its flat, wide entries to restaurants, shops and attractions; and Rome, where ancient architecture is now complemented by disability-friendly infrastructure. Also worth a mention are Tokyo, where most streets feature Braille markings to help people with visual impairments navigate – and Breda, in the Netherlands, which, according to a recent article in UK newspaper The Guardian, is the world’s most accessible city for its disability-friendly and wellness-focused facilities.

However, for every accessibility improvement made, there appear to be many more obstacles that remain around the world, from the uneven cobbled streets and narrow alleyways of many historic towns, to near invisible signposting or full-on noisy surroundings of others.

Rather than waiting for town planners and local councils to address these situations, it’s really down to employers to work with their would-be assignees to research and plan properly to ensure that they will not be held back by the local conditions.

It is essential that this process includes an audit of the expat’s place of work – where employers can fall short in many areas of provision.

‘Wheelchair access is sometimes completely unavailable unless the buildings are new-build – so it can be very difficult to access restrooms, eating facilities, and living facilities,’ says Ford.

‘And if someone has a relatively invisible disability, such as a health or mental condition, there is often no understanding whatsoever around the support structures required to enable these colleagues to be vibrant and productive in the workplace – such as having a privacy area for the employee for medicine or medical treatment they must have during office hours, appropriate space and accommodation to give that individual space.’

She adds that employers often neglect to provide devices needed to support employees with disabilities, such as wheelchair-friendly desks, as well as aspects such as easily navigable space for the accommodation of service animals or emotional support.

Generally, says Ford, too many businesses fall short when it comes to having comprehensive policies to support staff with disabilities on assignment and assignees can also misjudge the cultural adaptation it will take to relocate successfully for a job.

Patience and support from the company, and patience with oneself are critical

‘Companies and expats alike can really underestimate the cultural change required for expats, especially if they are moving to a country that has a similar language – an English speaker in the UK, in the USA, in South Africa, in New Zealand will all have very different experiences,’ she says.

If cultural training to help an expat settle in is important, for an expat with a disability it is indispensable. Ford says: ‘The first six months in a new country will be stressful, challenging, and outright frustrating as very simple day-to-day tasks can be very different from one country to the next. Patience and support from the company, and patience with oneself are critical.’

Businesses must provide expats with disabilities with a 360-degree package of holistic support, that involves the wider company, says Ford. This includes ensuring the company ‘updates policies; provides communication and awareness to the appropriate stakeholders and team members; develops and provides sensitivity and inclusion training to the company [managers, in particular]; and has regular and meaningful touch-points with the expat specifically around any concerns or issues they are facing and a commitment to follow up and support that individual and their family,’ she says. Flexibility is a key factor, she adds: employee and employer must work closely together to reach a solution that works for them both.

Working out clear and inclusive disability policies and support for expat assignments is the ‘right thing to do’; no-one should be disadvantaged whatever their specific set of needs. However, given that this may constitute ‘extra’ work and cost for businesses what do they actually gain from putting in the additional effort?

First, it means they will be fulfilling the requirements of the equality and diversity regulations of some nations as well as of an increasing number of their customers in the market. But beyond this, there are also huge benefits to businesses that truly embrace employees with disability.

To take just one example, in its research on hiring employees on the autism spectrum, global human resources organisation the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) says: ‘People on the spectrum often demonstrate trustworthiness, strong memories, reliability, adherence to rules and attention to detail.’

Meanwhile, Ford says inclusion and diversity of expats gives business access to ‘broader talent pools’ and to ‘great perspectives from people who would otherwise be marginalised’.

HR and mobility departments must devise packages that are tailored to the individual needs of employees with a disability who are relocating. This might mean including specific measures to assist them in their everyday life; allowing flexibility in the way benefits and allowances are implemented; or the lump sum option that allows their assignee freedom to specify their own support – however, if taking this last option companies must not ignore their specific duty of care to their employee.

FIDI Affiliates have a key role to play in helping businesses reassure and assist employees with disabilities, in areas such as researching support and services in the destination country, general orientation and searching for accessible homes and facilities. Those companies – particularly DSP providers – that adapt and promote their services in this area well will be invaluable, ensuring that expats with disabilities are better prepared for success in their overseas assignments and their employers enjoy the competitive advantage of having a more diverse and inclusive business.

This issue will be the subject of future articles and FIDI activity. To offer your comments and other input, please contact Magali Horbert at magali.horbert@fidi.org

Advice for expats with disabilities – and their businesses

- Find out about the country you are visiting.

- There are many websites offering accessibility advice for different countries.

- Do your research before setting out to do an activity. Do not assume that theatres, airports, restaurants, museums and other locations will be accessible. Ring in advance or check their facilities online.

- Keep your equipment in good condition. This may be more difficult when you are overseas – where your particular brand or model may not be supported. Ensure it is in good working order before you go.

- Look in advance for a reliable local supplier of any other equipment or medication you may need.

- Do not be afraid to ask for help. People are kind and, in general, willing to help – if you need help, just ask.

- Champion the cause. Be aware that you can help change attitudes by your personality, your resilience and your politeness. The way you act will not

only encourage people to help you,

it will pave the way for others with

similar disabilities.