Building a sustainable moving business needs a holistic approach that encompasses a company’s economic stability, the difference it makes to its people and local community, and having a mindset focused on improving as many lives as possible. Here, Dominic Weaver presents five perspectives

René Stegmann, Relocation Africa

“Financial stability will drive overall sustainability”

As a Zimbabwean now based in Cape Town, South Africa, René Stegmann, Director of DSP business Relocation Africa, understands the complexities of the southern African region’s social issues. The South African government’s Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) initiative, for example, aims to redress inequalities still lingering after apartheid and sees businesses bring ‘previously disadvantaged’ people into management and eventually stakeholder and ownership roles. However, while some companies are fully on board with the process, others do the minimum and fail to engage with the intention behind the programme. This means 16 years on from its introduction, sizeable economic disparities remain.

‘This is one of my biggest fears with sustainability and why I’ve become quite engaged with it,’ she says. ‘We can’t afford to pay lip service to sustainable development – until we all get on the same page, there is no real solution to any of this.’

The better news is that focus on doing the right thing from many different quarters is growing. If you don’t want to do things properly, says Stegmann, ‘don’t bother, because your intent will be seen by your work colleagues, your leaders, your clients and your supply chain. And you will very quickly be sidelined as a business’.

Given this, her advice to anyone planning to make their business more sustainable is ‘be authentic’. ‘I say to people you’re genuinely not going to solve poverty on your own, or through your business, or even your country,’ she says. ‘So do what you can to work towards what you can solve.’ In the African storytelling tradition, Stegmann illustrates this by recounting a local fable about a grandfather and grandson walking on a beach of stranded starfish that demonstrates this attitude to sustainability (see below).

What this means in practice for global mobility is to focus, not on box ticking – adopting standards or carbon offsetting for their own sake – but on looking to make genuine developments in a company’s mindset. ‘We need to look at the industry as a whole and make authentic change,’ says Stegmann. ‘Business used to be making money no matter what we disrupted from a people perspective; how much we paid them; how we treated them; what we did to the environment. Now business has to slide into the ecosystem of the world and it’s now “I have to be economically viable”, while considering people and planet. So, it’s a different lens through which we need to see our way forward.’

Economic sustainability is paramount, she says, and must precede environmental and social sustainability. ‘There is no point looking at the environmental impact our business is making if our business itself is not sustainable and standing well on its own two feet – economically viable and relevant into the future.’

Stegmann is a fervent advocate of transparency and working openly with both suppliers and clients to ensure cashflow is strong for everyone, a position strengthened by the challenges that were presented by COVID. She has committed to pay her own supply chain within 30 days and has approached clients, including RMCs, other DSPs and others to ask them for the same commitment. Fifty per cent of her clients are now paying within the time asked; she is working on the rest.

However, this is not about one company making a stand, she adds, it’s something the entire industry must do for the good of everyone in it – and is likely to involve some delicate conversations within the business.

‘We need to pressurise corporates. For our ultimate survival as businesses, we need first to be economically sustainable before we can go and spend money on making sure we’re environmentally friendly and people focused,’ she says.

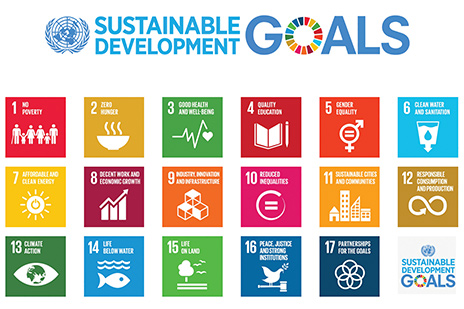

A business that has economic stability is free to develop its values and environmentally and socially sustainable operating practices. Using a framework and metrics such as those outlined in the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a business can also look at the difference it can make in any of these areas immediately and locally. This could include everything from tackling local poverty or hunger, launching educational initiatives to encouraging diversity or pay equality in the local community.

‘You can’t take a broad-brush approach to every country or business in the world,’ says Stegmann. ‘You need to educate yourself and your people about the SDGs; what they are and which ones you can address most urgently and which ones to address in the future… it’s going to be different for every business and country.’

Stegmann believes international mobility organisations have a central part to play in educating the industry, facilitating conversations and shaping the process of change. ‘All these industry bodies – FIDI, WERC, EuRA and so on – need to come together to help their members find solutions for the future,’ she says. ‘Through that collaborative effort and educating all the businesses involved, where and what we all need to be doing will evolve.’

The efforts of associations, their mobility business members and the people who work within them, will pay off by improving conditions locally and regionally, will help attract high-calibre staff who want to work for companies who make a difference, and add to the global movement towards positive change.

Ultimately, says Stegmann, it is the right thing to do.

‘None of us go to our deathbeds with money; we go there with our bodies, and that’s it. Through our journey between now and then all we need to do is something good, which makes us feel good and so when we die, we actually feel good about what we’ve left behind. So why not let’s work together and find solutions together?’

Derrick Young, BGRS

“Create a culture for change“

Change on sustainability is being driven by the business’s clients, says Derrick Young, Director of Transportation Governance at BGRS, but companies also need to create the right culture for change.

‘A lot of our clients are being driven by the principles of measuring and reducing and this does flow into their HR programmes and into company culture,’ he says. ‘We are also starting to have clients that are saying, we want to hire people with a mindset that is green… and we need to have flexible policies so they can choose a green move.’

This means developing more adaptable programmes for relocating employees, either as the lump sum or a basket of choices; for example, to use sea freight rather than air-freighted shipments or to not transport at all and rent furniture at their destination.

Driven by employees seeking forward-thinking companies to work for, employers are striving to make their jobs as desirable as possible. ‘Of course, this is part of equity, diversity and inclusion and not treating everyone the same – and the environment is one of the flexible options in policies now,’ says Young.

Part and parcel of this approach is companies taking a holistic view of their business, looking closely at the credentials of their suppliers, and asking questions including: Do they have an in-house sustainability programme? Are they measuring their carbon footprint? Do they have the right certification?

‘Big clients want to see the data,’ says Young. ‘They don’t want to see that you are ISO14001, they want to know how much you actually saved that they can put into their own bucket. But sustainable moving needs to be measurable in a way that also [takes in] those downstream suppliers. I can be ISO14005, but my agent in Costa Rica might not even recycle, so suppliers are a focus.’

Working with the right partners is a particular emphasis for larger companies, for whom every business they choose can help reduce their carbon footprint and boost their overall environmental performance. For movers themselves, Young says, their focus should be on providing what their clients want, in terms of clean vehicles and circular use of packaging – while making a difference in their own part of the world.

‘The world is too big when you’re a mover, so a big part is being a sustainability leader in your own market, in your own country or city,’ he says. ‘There are lots of ways you can do this – by allowing people time off for giving back to the community, such as clean-ups or helping with foster kids, all kinds of social programmes. That’s where movers can make a big mark.’

While smaller companies can’t necessarily have an impact that will noticeably change the global picture, by working with employees, they can certainly have a significant local impact. ‘What’s most important is that we create and environmental green mindset with everybody. So a company’s job is really to help foster that within its own organisation.’

As a final thought, Young says the mobility business needs standardisation of metrics to help it avoid risks and build sustainability in their operations. The next incarnation of FAIM – which is set to have a more robust environmental component – will help with this.

‘FAIM certification is so important to us as it gives some degree of accountability and control over how people are doing. [An environmental module] would help us a lot, because we have to manage our suppliers, our movers, to make sure they’re being compliant as part of our due diligence process,’ he says.

Andrew Wilson, Grace

“A national focus, with a structure we could leverage“

The pandemic highlighted what is critical to many businesses and what should be cut back, which included reappraising sustainability projects. For Australian Affiliate Grace, it helped increase the focus on what they really wanted to achieve from social responsibility initiatives.

Andrew Wilson, Group eCommerce and Marketing Manager at Grace, says the company’s previous sustainability programme involved funding several smaller organisations, which brought with it ‘horrendous’ administration and few opportunities to promote the business’s efforts. So, when COVID hit, the programme was halted, and priorities realigned.

‘We decided we needed a national focus, with an organisational structure we could leverage,’ he says, ‘and it needed to be not so large that our contribution would be lost.’

The upshot was a partnership with the Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF), an Australian national book industry charity that aims to increase literacy in remote Indigenous communities.

Demonstrating that a business is acting on sustainability is an increasing feature in tender documents globally. In Australia, the process of ‘reconciliation’ with Indigenous people is high on the agenda and this national issue aligned well with Grace’s wider efforts to ensure equal employment opportunities for people regardless of their gender, sexuality, ethnicity or other characteristics.

‘It’s about providing an opportunity for Indigenous participation in the business, particularly in some regional areas where there are large communities; and providing things like traineeships, extra assistance or encouragement to develop a career path and just to make your workspace a more welcoming place,’ says Wilson. ‘Non-Indigenous Australians are becoming more conscious of this issue and we’ve seen some big shifts in reconciliation with First Nations peoples. The narrative is changing and corporate Australia has really risen to the challenge in the last few years.’

Like some big business in Australia now, Grace flies the Aboriginal flag outside its headquarters and uses Indigenous place names as a part of the addresses of its facilities. However, Wilson says this would be ‘window dressing’ without meaningful action taking place.

The company has also formed an Indigenous working group made up of key managers and chaired by an Indigenous staff member to help ensure this happens.

Paul Barnes, Inspire Global Mobility Consulting

“Use a framework, measure and promote”

Paul Barnes, of Inspire Global Mobility Consulting, says: ‘Clients are putting increasing pressure on their suppliers to be sustainable in every sense, including environmental and social.

‘This is flowing from financial markets and consumer pressure to the boards of corporations, through their companies, resulting in them appointing sustainability officers to drive the environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda in meaningful ways. This flows to management, and out to the supply chain.’

However straightforward this pathway appears, when it comes to measurement of and action on sustainability, companies must take a realistic view of the size of the job at hand, says Barnes.

‘We can’t ignore, and need to understand, the complexities of sustainability, the world that we live in and deliver services in. From this, we get an understanding of what is and isn’t achievable in a certain timescale – and most importantly why. It is essential that providers have this clear in their minds and educate their clients on it, too.’

Like others, Barnes says businesses should take a recognised platform such as the UN Global Compact as a framework for their sustainability drive. From here, they can sign up and develop their own company-specific roadmap, based on what they are able to achieve and by when.

For this to work, he adds, having credible data measurement is essential. He says: ‘Companies are currently working with different sources to have their mobility service data analysed and to obtain CO2 data. This is mainly based on HHGs and travel but will move to other services.’

And, if you’re doing the improvement work, let people know, in as many ways as possible: ‘Social media, direct to clients, to the relocating employee and internal education to staff/supply chain,’ to name a few. ‘There is a huge opportunity to promote this to multiple stakeholders within the client’s organisation as they are all interested in sustainability, and stakeholders in driving sustainable solutions,’ says Barnes.

Ben Ivory, Graebel Companies, Inc

“Take clear and practical steps”

Ben Ivory, Senior Vice-President at Graebel Companies, Inc, says he is excited by the growing focus on sustainability, which has been accelerated by the past turbulent few months.

He says: ‘The past two years’ events, including the pandemic, created a tipping point where now dialogue is occurring, information is being shared and tangible steps are being taken to change individual and organisational behaviours.’

For FIDI Affiliates wanting to create a sustainability programme, Ivory suggests five practical steps:

Identify your leader(s): ‘A successful company sustainability initiative needs ownership commitment but also needs (at least one) company advocate who can be learning about sustainability programmes, looking for new ideas, and learning from clients and organisations such as FIDI.

‘Ideally, the leader has operational responsibilities and can participate in purchasing decisions regarding packing materials or vehicles and to ensure new practices are implemented by those on the front line.’

Take inventory of current sustainability practices: ‘These may be current recycling programmes or traditional ways of doing business, such as use of reusable furniture pads that can be refreshed or expanded. Affiliates likely have a good start and a foundation to build on.’

Identify high impact opportunities: ‘Most HHGs providers’ best opportunities are in the vehicle transportation category or in the operation of facilities/warehouses. Identify and prioritise opportunities and review options. Formal or informal discard and donate programmes are easy to implement, for example; they immediately reduce carbon emissions and may be new sources of revenue.’

Research tools to measure your carbon emissions: ‘Increasingly, the focus is on measurements and goal setting. Many tools are available. Some are basic, others more sophisticated. In the US, for example, our federal US EPA offers many tools and resources (see www.epa.gov)’

Be realistic: ‘This is a long-term issue. If you try to do too much at one time, programmes and people burn out.

‘The word sustainable is defined as “able to be maintained at a certain rate or level”. Saying it another way, “good things take time”.’

To conclude, Ivory celebrates the united spirit already fostered in the mobility business, which he says can make for a smoother process of change.

‘As we work together to respond to incredible challenges, including the threats of climate change, let’s take time to remember how fortunate we are to have FIDI as our forum to collaborate,’ he says. ‘Our industry has worked effectively together for 70 plus years. We can leverage our strong relationships to be true leaders to make a more sustainable world for future generations.’

The starfish story: do what you can

‘A grandfather and grandson were walking on a beach, where a tide had washed in thousands upon thousands of starfish, which were stranded.

‘As they were walking along, the small boy started running ahead, throwing the starfish into the sea.

‘The grandfather said: “You know with all these starfish, you’re really not going to make a difference to them.”

The boy turned around, picked up another starfish, threw it back into the sea, and said: “But I made a difference to that one.”’